ITCH / SUPERSTITION

Both sensations and beliefs are a mix of reality and hallucination.

There’s something curious I noticed about itch. Not the kind of strong itch produced by a mosquito bite or a healing wound, but the brief, ephemeral sensation that occasionally tingles the skin for no obvious reason and disappears completely after being scratched. Most of the times it’s so quick and barely noticeable that I scratch it without even registering. But sometimes, when I am trying to fall asleep and there are no other pressing tasks or thoughts, I do scratch the itch consciously, and when I do, the itch instantly reappears somewhere else on my body. Usually that new itch is even weaker than the original, but still noticeable if I pay attention. If I scratch that second itch, a third appears, and then a fourth, and so on until I finally stop scratching and just let it go for a few seconds — as soon as I stop thinking about it, it goes away.

As it turns out, I’m not the only one: one in five people experience the same sensation, termed “referred itch”. It has been documented in scientific literature, although no one seems to have a great explanation for it. The reason I find it so interesting is that this referred itch is obviously not real — just the fact that it randomly jumps from arm to leg to shoulder to eyelid in a span of a few seconds clearly tells me that there’s nothing specific going on with my skin in either of those places — maybe the original itch was caused by a bit of dryness, but the rest is clearly a mirage. It feels as if after I scratch the first itch, my body really wants something else to itch, and so it keeps making it happen.

Itch, as a matter of fact, is a sensation that’s uniquely malleable. It feels physical, grounded in reality, like the senses of touch or pain, but compared to pain, itch is more psychosomatic — for example, it is more easily relieved by placebo and more strongly induced by nocebo, or even verbal suggestions that something should be itching. In other words, itch is always a bit of a hallucination. This is why it can be contagious: we see someone scratching, imagine the sensation, and start itching ourselves. It’s also why itch is a common symptom of several psychiatric conditions.

My own referred itch reminds me of something very specific: social media compulsion. I bet you have experienced this, too: if you post something and get a few likes right away, your brain immediately comes up with another thing to post.

What could be the connection? The most obvious answer is — reward. It feels good to scratch, and it feels good to get social media likes, so we want more of it. But reward doesn’t always work like that. Imagine receiving all your likes at a specific time once a week, like a salary. This would not only not motivate you to post more — you would probably come to dread the day the likes arrive.

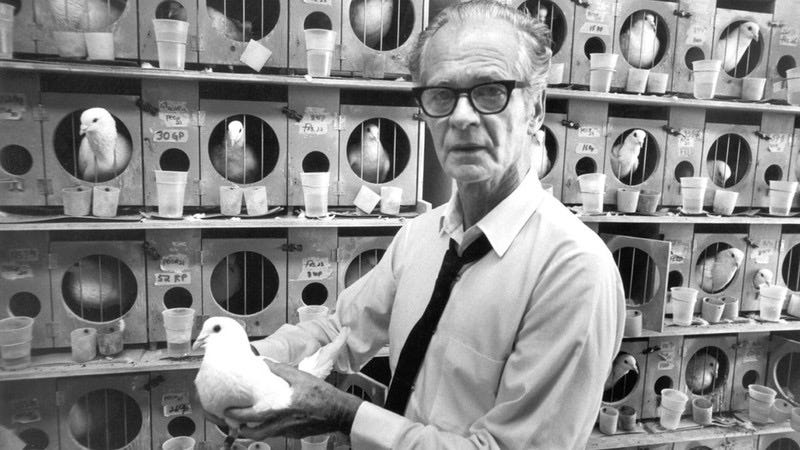

The key difference between the two scenarios is predictability. Let’s say you train a pigeon to peck a button to get access to food. Then you start changing how many pecks it takes. Now, if you make it a fixed number — say, fifty pecks per reward — the pigeons will seem pretty tired every time they finally get it, and for a while be uninterested in the button before they start pecking it again. The more pecks you require — the longer the pause. But if, however, you make the number of required pecks random, then the pigeons seem much more energized. They don’t stop after getting the reward. They keep pecking, and pecking, and pecking without pause, even if they end up doing more work than the tired pigeons on the predictable pecks-per-reward program.

The most astonishing, even creepy thing about these pigeons (or other animals — this is not specific to birds) is that you can get them to believe that they actually have control over the process. This is called autoshaping: let’s say, you install a button in the cage, but the button doesn’t actually do anything, and instead the reward appears at random times. Although the button has no connection to the reward, as the experiment progresses, more and more pigeons start pecking it, and eventually, after a few days of random reward deliveries, literally all of them do. Basically, pigeons gradually become convinced that their irrelevant actions are necessary for the reward arrival. They develop superstitions.

Unpredictability draws us in. It makes us imagine things, and distorts our perception. Whenever our brains find something they can’t quite predict, they dig in, double down, go all in to try and figure out the pattern, and when there truly is no pattern to figure out — they imagine it. B. F. Skinner, whose groundbreaking work on pigeons I described above, pointed out that this is why a slot machine, and gambling in general, is so addictive. It is also why social media are so addictive — not only is there unpredictability in how your friends respond to your posts, but the likes are also designed to arrive at random times, so that we are always on our toes.

Is it, then, what makes itch hop from one part of the body to the next? Could it be that because this faint itch has no obvious reason and seems to pop up randomly, the reward — the pleasure of scratching — also arrives randomly, and the brain digs in, trying to crack the pattern? Because itch is already part hallucination, the very act of trying to find it somewhere in the body recreates it — again and again, until you consciously break the cycle. If this were true, it would make itch a kind of embodied confirmation bias.

How would we know if my theory is correct? We need to look for further connections between itch and higher cognitive function. Does itch truly have the same nature as a perception bias? We already know that psychiatric disorders like schizophrenia can increase itch hallucinations. We also know that some antidepressants can help people with severe itch but no skin issues. What about healthy people with different personalities? Is there, for example, a correlation between referred itch and superstition? (I don’t consider myself superstitious, but I certainly am impressionable, which one could say is a secular version of the same thing.) As far as I know, no study has investigated such an unlikely connection. Do chemicals that affect mood, motivation, or problem solving in healthy people, also affect their propensity for itch, or specifically the referred kind? Do neural pathways associated with itch overlap with pathways responsible for cognitive distortions?

If indeed a connection was established, it would not only bridge two unlikely fields of psychiatry and psychology, but teach us something important about our inner worlds: that whether it is our belief systems or our skin sensations, our mind is always a mix of reality and imagination.

The worst part is when you feel an itch but can’t say where…

For many years, I was wondering what on earth was happening when I couldn’t fall asleep and would lie in bed for a long time, only for different parts of my body to start itching one after another. Then, that’s exactly what kept me from falling asleep. Thanks for the revelation!