LANGUAGE MODELS / MEMES

Will ChatGPT allow us to communicate with thoughts?

I saw this ad in the subway this morning and I kept thinking about how amazing language is. People tend to think of it as a collection of words and their meanings, but there’s so much more — an implied, shared understanding that provides critical context, and that context can be vastly more complex than the meanings of the words themselves. You could say that word definitions are just a tip of the iceberg. Imagine reading this out loud to someone a 100 years ago — would they even know what is being advertised? (“Our best-selling Watermelon Glow PHA+BHA Pore-Tight Toner” — this entire phrase refers to one substance!)

To illustrate my point, here are Google Ngrams for the words “glow” and “dewy” (a more common word form in the context) — they follow the trend for the word “skin” and emerge in the 2000s on the wave of farm-to-table millennial hipsterdom (Goop was founded in 2008).

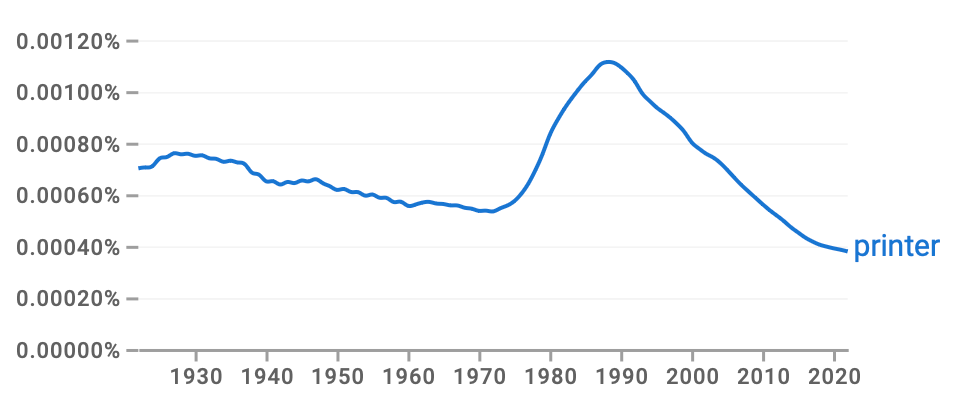

The word for “toner”, meanwhile, closely follows the trend for the word “printer”, peaking in the 1990s and rapidly falling back to baseline as personal printing waned from our lives — that leftover bump in the graph for “toner”, which is missing in “printer” is probably the cosmetic toner from the ad — I’m not sure Gen Z even knows what laser printer toner is.

So language is not just a list of words and the objects they correspond to. What we mean by different words is a massive trove of information that constantly changes, over the course of our lives and even within a single conversation. Words can be used literally and figuratively, for example — in the ad, the word “glow” refers both to shiny skin (“dew you”) and overall cheerful demeanor (“confident, glowing self”). For another example, consider the word “sick”: it could mean that someone has a disease; that someone is morally corrupt; or that something is exceptionally good — what you actually mean depends on the context, tone and style of speech.

A common criticism of large language models, which power chatbots such as ChatGPT, is that they don’t really understand language like our brains do, but simply predict which word should come next in sequence. But a new study by a team of Princeton researchers shows LLMs are, in fact, the best model of how our brains actually store language in the physical format of neurons and synapses.

LLMs don’t just analyze word sequence probabilities. They also map how words relate to each other: contextually, semantically, grammatically, and maybe even in ways we don’t have terms for. You can imagine an LLM as a multidimensional virtual space, in which each dimension is some feature of language, and words are nodes within this space.

In the study, this virtual space was used as a common ground between two people talking to each other. Previous research has shown that brain activities of speakers and listeners "synchronize" during conversation, the activity in the speaker predicting the activity in the listener a moment later. The new study mapped these activities onto the LLM's multidimensional space, assigning specific meanings to brain responses and giving them a precise, mathematical formulation. This LLM-based mapping outperformed other models in predicting how well speakers’ and listeners’ brains synchronized. And so, for the first time, researchers were not only able to show a neural connection between a speaker and a listener, but interpret the content of this connection.

What does this mean? There are immediate implications and some more far-fetched ones.

First, saying that LLMs “simply predict which word comes next” does not really do them justice. If that’s how you choose to describe LLMs, you must now conclude that our brains do the same: choose which word should come next based on complex, context-dependent, multidimensional linguistic relationships.

Second, distinct patterns of brain activation in speakers and listeners can evidently be converted into shared words — and so, in principle, mapping brain activity onto an LLM could be a viable path to communicating with thoughts. Right now words can only be guessed with a low probability — better than chance, but nowhere near good enough for conversation. To reliably guess words from brainwaves every time would require much more sophisticated brain scanning technology than EEG used in this study (which is a bit like listening to the ocean from the shore and trying to piece together a conversation on a distant ship).

But there’s a third, less obvious implication: this marriage of brains and LLMs should breathe new life into the field of memetics — the scientific study of memes.

The concept of memes — cultural equivalents of genes — was introduced by Richard Dawkins in his 1976 book “The Selfish Gene”. Dawkins likened the evolution of culture to the evolution of biological species: just like genes, memes are “copied” (imitated) with variation and selection, leading to Darwinian evolution. So evolve fashion trends, musical genres, art traditions, speech patterns. Memes in the common understanding of the word — funny pictures based on a reproduced template — are just one type of meme in the broader sense.

For decades, the criticism of memetics as a serious scientific field has been that memes are too vague of a concept to be useful. By definition, a meme, like a gene, is a piece of information that is repeatedly reproduced in new physical form. But a gene is simple: you can point to a stretch of DNA and say “here’s the gene”. You can find that same gene in another individual and point to it too — they would look the same, or very similar. You can’t do it with a meme: our brains are all different, and you can’t simply identify the same exact neurons in person A and person B. Besides, memes reside not simply in a particular neuron or a group of neurons, but in a specific configuration of a vast neuronal network — a much more complicated physical substrate than a string of DNA. Today we can perhaps identify a brain region responsible for thinking about fashion trends, but we can’t, as of yet, tease apart a network configuration that says “skinny jeans” from a network configuration that says “baggy jeans”. So memes, goes the argument, are a purely theoretical concept.

But I think the best evidence that memes are physically real is the fact that units of culture, including fashion trends such as skinny and baggy jeans really do come in waves that transcend individual people — something is being copied from brain to brain, even if we don’t have the proper tools to mathematically account for it. Yes, brains are all different. They are all independently sculpted out of unique and chaotic tangles of neurons. But the sculptor — human experience — is, in many ways, consistent across individuals. And so our brains all end up encoding the same cultural content — styles of jeans, meanings of words — even if they do so using different neurons. These consistent encodings of cultural content across multiple people are the memes.

Now, for the first time, we have a way of turning some of that cultural content into data, and a way to relate the data to neural activity. It is not the same as finding the memes in the brain yet. But it is a step in this direction — once we have a precise way to know what information we are looking for, we might just be able to find where in the brain it is encoded. In hindsight, we might remember LLMs as a stepping stone into a world of memetics.

To imagine what that world would be like is a bit like trying to picture genetic engineering before DNA was discovered. So maybe that’s the best analogy: just as genetics rendered all past accounts of inheritance obsolete, memetics will render obsolete all existing forms of sociology, marketing, political science, and P.R. When memes are as precisely understood as genes, we will begin to see culture not as a disjointed composite of chance and individual decisions, but as a unified, living, evolving organism in its own right. We will understand that every idea is a reshuffle of previous ones. We will be able to parse our own minds into distinct components, identify their sources, and trace the evolutionary tree of each thought. On the scale of humankind, we will be able to identify the precise causes of faulty memes such as climate change hesitancy, or conspiracy theories, and work out how to best combat them. Of course this power can be used for coercion and profit, too: current algorithms of social media targeting and tools of state propaganda will pale compared to the level of mind control that will be possible once we understand the physical nature of memes.

All these ideas sound like moonshine today — but at one point, so did genetics, let alone machines that talk.

Can machines have memes? How do memes relate to the sparse connection in our brain, possibly generated by our unconsciousness(which I think is the association we didn't notice)?