The Mozart effect is back in the news: a new study claims to show that Western classical music helps people with treatment-resistant depression by lifting their mood.

“Whether Bach, Beethovan [sic!], or Mozart, it's widely recognized that classical music can affect a person's mood” — begins the news article on Science Daily. (At least I know it was written by a human.)

Actually, it is not widely recognized. Personally, I think it is preposterous to believe that our brains have evolved to seek some Platonic ideal of sound that only Western European composers in the 1700s were able to achieve, and only with Western instruments. But let me set my opinion aside and review the evidence.

First, let’s look at the paper in question, which was published this week. It is a study of 23 patients, all of whom had undergone treatment for severe depression, but the treatment didn’t help; they all had electrodes implanted in the brain for deep brain stimulation (the stimulation was not performed in this study specifically, but it says something about the participants that they were at the point of implanting electrodes into their heads.) These patients all indicated that they had never listened to classical music (to quote the paper: “lacked prior exposure to classical music appreciation due to their Asian cultural background”) and were not familiar with the two pieces of music used in the study: Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 6 (“representing sadness”), and the third movement of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 7, (“representing joy and excitement”). First the researchers played the two pieces to 13 people — it’s not clear for how long and how many times (“The quantity, duration, and frequency of the music treatments varied slightly depending on the patients' grouping conditions.”) Then, they asked these patients “please describe the level of your current depressive feelings” or “please describe the level of your current anxious feelings” and had them drag a slider on the screen between 0 and 100. They expected that happy music would make people happier and sad music would make them sadder, but there was no difference.

Then, the authors took the remaining 10 people and had them listen to an 8-track playlist for two weeks, three times a day. The playlist included, besides Tchaikovsky and Beethoven, pieces from Bach, Mozart, Vivaldi, Schubert, and Pachelbel. In the end, participants gave each piece a score for how much they liked it. Researchers then picked, for five patients, the most favorite piece, and for the remaining five, the least favorite piece; played it to them; and asked them to report their depressive/anxious feelings. Huzzah — “low enjoyment music” scored way higher on depression and anxiety than “high enjoyment music”!

For the rest of the paper, the authors then abandon any comparison between Tchaikovsky and Beethoven and go on to show that this “high enjoyment music” changes activity patterns in the reward system, which is to be expected when you, you know, enjoy the music.

There is nothing wrong with the data, but to suggest that this is somehow about the superiority of Western music, let alone that it’s a magical cure for depression, is ridiculous. First of all, I will never believe that none of the 23 people had any familiarity with Western classical music. Unless they come from an uncontacted tribe in the highlands of New Guinea, there’s no way they have not been exposed to Western musical canons: in movie soundtracks, in Disney cartoons, in commercials, in sports. Next, put yourself in the patient’s shoes. You have been battling clinical depression for years. Now these scientists are asking you to help them with a study of music. Sure, you say. They give you a playlist of 8 generic classical pieces. You listen to them, like, forty times. Some you like, some you don’t, but you have to keep listening — for two weeks! Then, the scientists ask you to ID your least favorite piece. You pick the one that’s been annoying you all this time. Then they put you in a room, give you headphones, and play that very piece that you just said you hate. And then they ask you how depressed you feel and ask you to run a slider from 0 to 100. What would you do? I’m pretty sure I’d run the slider to 0 regardless of whether I’m depressed and regardless of what kind of music you gave me — just stop already! All this experiment shows is that when people are played the music they said they like, they say they are less depressed and anxious than when you play them the music they said they hate.

But the biggest issue with this entire genre of research, in my opinion, is that there is hardly ever any comparison of Mozart and Bach with any other kind of music. It is especially frustrating to see this in studies coming from non-Western backgrounds, such as in the study above by researchers from Shanghai.

Mozart effect’s big moment came in 1993, when Raucher et al. published a paper showing that after listening to Mozart's sonata for two pianos (K448) for 10 minutes, normal subjects showed significantly better spatial reasoning skills than after listening to relaxation instructions designed to lower blood pressure, or silence. The effect persisted for no longer than 15 minutes after listening, and did not affect skills other than spatial reasoning. No other type of music was tested, and even these results proved controversial and difficult to reproduce. Why was the K488 sonata picked? Because Alfred Einstein called it “one of the most profound and most mature of all Mozart's compositions.” (Can you get more Eurocentric than that?) Raucher et al. went on to publish another paper showing that classical music training (as in, learning to play a piano) also improved spatial reasoning skills, and another study showed that it also improved mathematical reasoning. There was no comparison with other instruments or genres of music.

What do we know about other types of music and how they affect performance? Pathetically little. We know that relaxation instructions don’t affect spatial reasoning, but that’s not music. One study has used a bizarre cocktail of sonic experience: on day 1 participants heard “a minimalist work by Philip Glass” (unspecified); on Day 2 they heard “an audio-taped story” (unnamed); and on Day 3 they heard “a dance (trance) piece” (neither producer nor track indicated). This strange mix did not improve spatial reasoning in the same way as Mozart’s sonata did. In another study that explicitly sets out to test the generality of the Mozart effect, the same K488 sonata is compared, implausibly, to a single song by a Greek singer Yanni, because, the authors explain, “the work is similar to the Mozart piece in tempo, structure, melodic and harmonic consonance, and predictabhty.” Apparently, Yanni also works.

Maybe the most convincing indication that there’s something specific about Mozart is this study of epileptic patients, in which the Mozart piece was shown to reduce epilepsy-like activity in the brain. On close inspection, however, we once again find out that the study barely touched any other music. What they use as a control is something they call “Old Time Pop Piano Tunes”, and there is no systematic comparison between that, and Mozart. This is the only diagram from the paper that has both Mozart and Old Time Pop Piano Tunes side by side:

So, there’s some response to Mozart in this one patient’s right hemisphere when you start playing the sonata — it goes away in about three minutes before you stop playing, though, and then does not reappear when you start playing Old Time Pop Piano Tunes. We don’t know if this is a consistent difference.

More importantly, though: what the hell is Old Time Pop Piano Tunes? I tried searching for the phrase on Spotify and YouTube to no avail. This is what amazes me about the entire notion of the Mozart effect. Have these people never listened to any music except their Bachs and Mozarts? Why can’t we construct a normal, informed study of musical enjoyment and familiarity’s effects on cognition based on something a little more nuanced than “classical music is good for you” and “trance is repetitive”? Now that we have generative AI, you could easily produce hundreds of unique musical pieces with varying instrumentation, mood, timbre, rhythm, and so on. It is time to get serious about music.

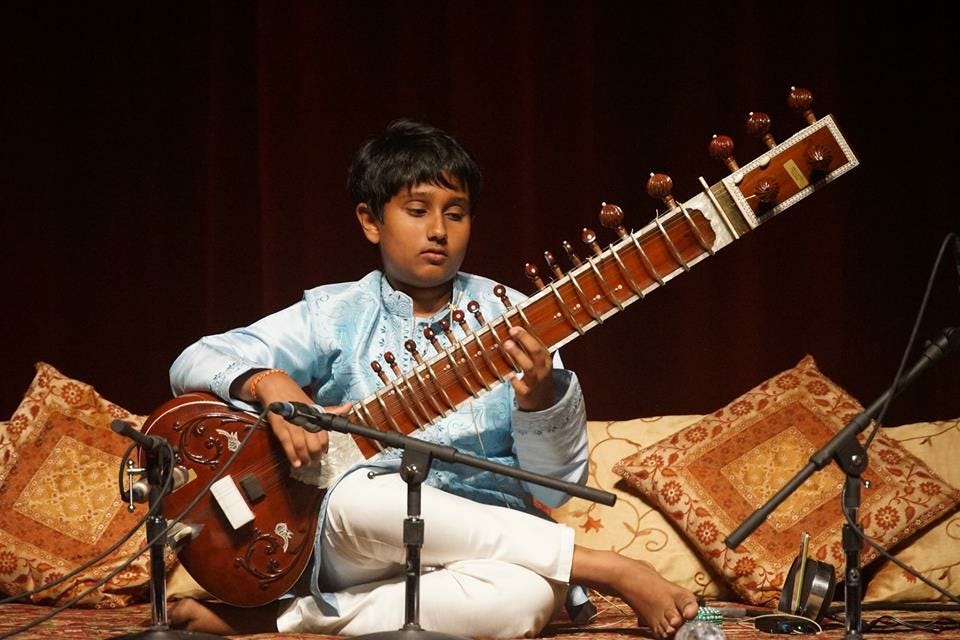

As someone who grew up in operas and philharmonics, having absorbed the unspoken assumption that classical music somehow makes you a better person in a way that “dumb” music doesn’t, I might have a special aversion to the notion of the Mozart effect. To me, it is an element of faux aristocratic decorum, like a marble print on a toilet seat — something that culturally insecure parents in Asian countries entrain on their children out of misplaced ambition. It reeks of colonialism, mothballs, and tweed. I share my favorite music critic Simon Reynolds’ aversion to “intelligent” music and am always drawn to “base” genres — from klezmer to gabber — no doubt because I am pushing back against my own childhood.

But regardless of my opinion, I think it is time to cut Mozart out. If studies show that the Mozart effect can be induced with the Greek singer Yanni, are we really going to continue saying that’s because Yanni is similar to Mozart?